- Introduction

- What is gendered language?

- The English language

- The issue of gendered language in the workplace

- The bias problem with natural gender language

- Natural language gender bias in the workplace

- Ways to reduce gender language bias

What is gendered language bias, and how can we reduce bias in job descriptions?

Introduction

If, during a recruitment cycle, someone described one candidate as ‘ambitious’ and another as ‘empathetic’ or ‘kind’, which do you think you would be more likely to hire? Unless hiring for a caregiving role, its likely you would have a preference for the former candidate, demonstrating the power of gendered language in shaping how we think and behave. “Gendered language is understood as language that has a bias towards a particular gender [and] reflects and maintains pre-existing social distinctions,” explains Roxana Lupu, an expert in applied linguistics. Gendered language bias is prevalent in everyday communication and influences workforce behaviour and decisions, reinforcing gender stereotypes, but to what extent? And how can we minimize this?

What is gendered language?

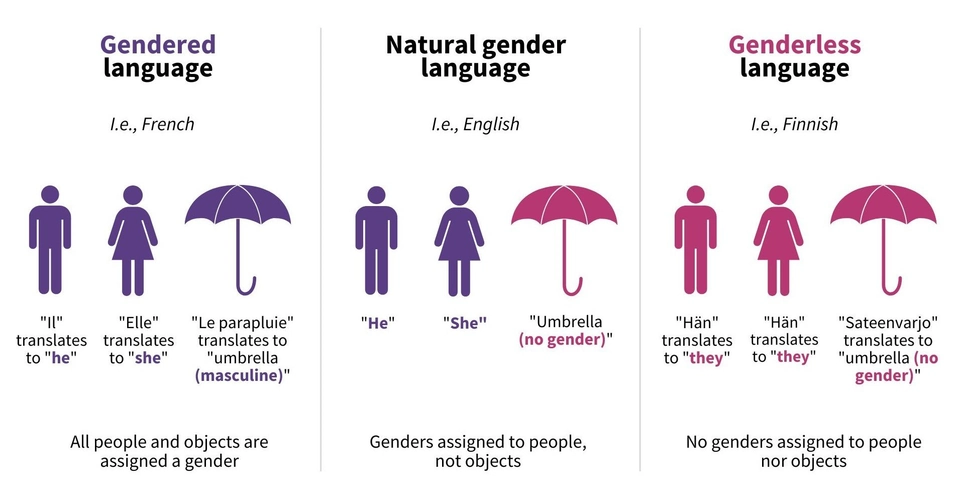

Language typically falls into three categories – gendered, genderless and those termed natural gender.

-

Gendered language: all nouns and pronouns are assigned a gender which is usually feminine, masculine, or neutral (i.e., French and Spanish).

-

Natural gender language: only people are assigned genders (i.e., English).

-

Genderless language: no mention of language. Descriptions are of whether something is animate, inanimate, human or non-human etc (i.e., Finnish, Estonian and Hungarian)

The English language

The English language is a natural gender language, meaning gendered language is only used when referring to a persons pronouns, e.g., “The doctor will see his patient” conveys that the doctors gender is male. A slight exception to the rule is when gender-specific terms referring to someone’s profession exists. For example, the nouns “businessman” or “waitress” indicate the employees gender. The issue with these terms is often referred to as the “historical patriarchal hierarchy”, whereby a man is considered the norm, and a woman is considered to be different. Why was the English language developed this way? The English language was written at a time when only men were considered people, and so humans were referred to as “man” and terms like “man-size” and “mankind” were coined.

The issue of gendered language in the workplace

To put it simply, gendered language leads to bias and gender inequality in the workplace. In 2018, the World Bank analysed data from 4000 languages (accounting for 99% of the global population), and concluded that gendered language was consistently associated with female labor-force participation [1]. Moreover, in countries where gendered language is spoken, there appears to be less gender quality [2]. Research has also identified a relationship between gendered language and explicitly sexist views in the workplace, with employees in these countries more likely to agree with statements such as “On the whole, men make better business executives than women do” or “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.” [3]. This is because often words describing a role itself, or the competencies required are tailored towards different genders.

The bias problem with natural gender language

Although in the English language, roles and affiliated words are not explicitly assigned a gender, stereotypes, and, therefore, implicit associations persist. This means some roles are deemed more suited for different genders, reinforcing the social inequalities between men and women. For example, it is often believe that women show traits of being “warm”, “kind” and “loyal”, while men are perceived as “confident” and “ambitious”, as is often reflected in the lexical choices of everyday communication. Interestingly, regardless of how desirable these traits are for a role, men and women are often viewed unfavourably when exhibiting characteristics typically associated with the opposite gender. Meta COO, Sheryl Sandberg speaks of this as she recalls being labelled “bossy” as a younger book, where a boy would have been praised for having “leadership skills”.

Natural language gender bias in the workplace

Implicit gender bias associations in natural languages can attract or deter different applicants, reinforcing unhelpful gender stereotypes. For instance, Total jobs analysed over 75,000 job adverts and found that masculine coded words were most commonly used across science, sales and in senior positions, while female coded words were commonly found across care roles and hospitality [4]. These findings feed the idea that men should lead, and females should have supportive positions. Another study looked further into this and found that STEM roles were advertised using masculine language in Scotland, where men make up 75% of the STEM positions, which put equally qualified women off applying [5]. When feminine language was used to describe the same role in this study, however, women were more attracted to the job description. Interestingly, the use of gendered language is so subtle that none of the participants in the study even recognised the use of language and the impact it had on their interest. To understand the extent of the problem: it was recently revealed that over half (52%) of UK job adverts are phrased with gender biased words [6], and another study found that women are 50% less likely to consider roles that have a coded gender bias in the advert [7]. This means a quarter of the UK female population are put off applying for roles based on gender coding in the job description alone.

Ways to reduce gender language bias

Gender language bias is subtle, however it can be preventable. When communicating internally/externally as an organisation, consider word choice, structure and tone. For instance, find neutral alternatives to needlessly gendered words: “waiter” becomes “server”, “businessman” becomes “business-person” etc. Another way is to practice using gender neutral pronouns: “He needs to talk to his client” becomes “they need to talk to their client”. When writing job adverts, consider the choice of wording and ask yourself “what gender will this advert likely attract?”. Useful tool for this are Eplor and Gender Decoder, which review job descriptions and recruitment material for any gendered language, and makes recommendations on how to widen applicant pool by eliminating unconscious bias

Author: Emma Bluck (Marketing and Scientific Communications Lead)

Start Building a Fairer Workplace With Us

Dive into the future of work with our expertly crafted solutions. Experience firsthand how MeVitae’s AI-driven solutions can make a difference. Request a demo or consultation now.